Quotes from this essay (also here):

Both genres have ancient lineages. Utopia goes back to Plato at least, and from the start it had a relationship to satire, an even more ancient form. Dystopia is very clearly a kind of satire. Archilochus, the first satirist, was said to be able to kill people with his curses. Possibly dystopias hope to kill the societies they depict.

By that definition, dystopias today seem mostly like the metaphorical lens of the science-fictional double action. They exist to express how this moment feels, focusing on fear as a cultural dominant. A realistic portrayal of a future that might really happen isn’t really part of the project—that lens of the science fiction machinery is missing. The Hunger Games trilogy is a good example of this; its depicted future is not plausible, not even logistically possible. That’s not what it’s trying to do. What it does very well is to portray the feeling of the present for young people today, heightened by exaggeration to a kind of dream or nightmare. To the extent this is typical, dystopias can be thought of as a kind of surrealism.

These days I tend to think of dystopias as being fashionable, perhaps lazy, maybe even complacent, because one pleasure of reading them is cozying into the feeling that however bad our present moment is, it’s nowhere near as bad as the ones these poor characters are suffering through. Vicarious thrill of comfort as we witness/imagine/experience the heroic struggles of our afflicted protagonists—rinse and repeat. Is this catharsis? Possibly more like indulgence, and creation of a sense of comparative safety. A kind of late-capitalist, advanced-nation schadenfreude about those unfortunate fictional citizens whose lives have been trashed by our own political inaction. If this is right, dystopia is part of our all-encompassing hopelessness.

Sometimes I feel like this. While I genuinely enjoy dystopian literature, I often come away with the feeling that it's far too often "at least my life isn't this bad." And we're also seeing this now, with regards to the use of dystopian literature as a way to express things that are happening.

The constant use of The Handmaid's Tale is infuriating. First because it's constantly non-disabled cis white women pulling the story to highlight what is being done to them now, having ignored the plight of all others: Black women, Latinas, GRT/Romani/Sinti women, Indigenous women, and so many others have had their bodies legislated in ways that cis white women never have and never considered. Trans and non-binary people have all had their access to relevant healthcare and reproductive needs restricted simply for who they are, while trans women in particular (and even butch cis women) have had their access to restrooms legislated. Disabled people (especially women) have had to deal with being sterilised and being told that they "shouldn't be selfish" and have children.

Every single group has had their body legislated and monitored to some extent, but now non-disabled cishet white women are finally on the receiving end... So they pull this singular tale as a "what has happened now," refusing to engage in the history they've ignored.

But for so long, while it should've acted as a warning, people saw it in the very way Robinson states: "At least my life isn't like that." While I don't blame the book for this, so many people refused to engage with it critically and most certainly turned towards complacency. In some ways, this is is mirrored:

On the other hand, there is a real feeling being expressed in them, a real sense of fear. Some speak of a “crisis of representation” in the world today, having to do with governments—that no one anywhere feels properly represented by their government, no matter which style of government it is. Dystopia is surely one expression of that feeling of detachment and helplessness. Since nothing seems to work now, why not blow things up and start over? This would imply that dystopia is some kind of call for revolutionary change. There may be something to that. At the least dystopia is saying, even if repetitiously and unimaginatively, and perhaps salaciously, Something’s wrong. Things are bad.

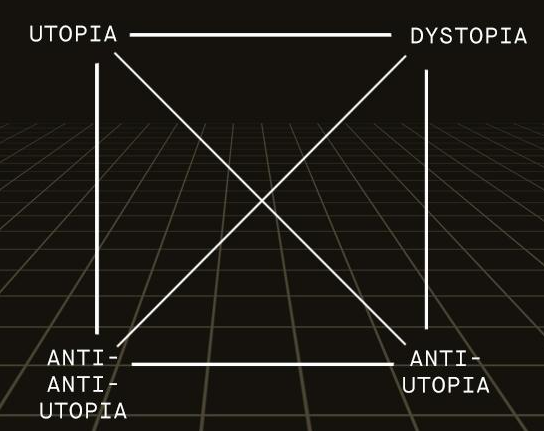

It’s important to remember that utopia and dystopia aren’t the only terms here. You need to use the Greimas rectangle and see that utopia has an opposite, dystopia, and also a contrary, the anti-utopia. For every concept there is both a not-concept and an anti-concept. So utopia is the idea that the political order could be run better. Dystopia is the not, being the idea that the political order could get worse. Anti-utopias are the anti, saying that the idea of utopia itself is wrong and bad, and that any attempt to try to make things better is sure to wind up making things worse, creating an intended or unintended totalitarian state, or some other such political disaster. 1984 and Brave New World are frequently cited examples of these positions. In 1984 the government is actively trying to make citizens miserable; in Brave New World, the government was first trying to make its citizens happy, but this backfired. As Jameson points out, it is important to oppose political attacks on the idea of utopia, as these are usually reactionary statements on the behalf of the currently powerful, those who enjoy a poorly-hidden utopia-for-the-few alongside a dystopia-for-the-many. This observation provides the fourth term of the Greimas rectangle, often mysterious, but in this case perfectly clear: one must be anti-anti-utopian.

The reference Greimas rectangle is the following:

Besides, it is realistic: things could be better. The energy flows on this planet, and humanity’s current technological expertise, are together such that it’s physically possible for us to construct a worldwide civilization—meaning a political order—that provides adequate food, water, shelter, clothing, education, and health care for all eight billion humans, while also protecting the livelihood of all the remaining mammals, birds, reptiles, insects, plants, and other life-forms that we share and co-create this biosphere with. Obviously there are complications, but these are just complications. They are not physical limitations we can’t overcome. So, granting the complications and difficulties, the task at hand is to imagine ways forward to that better place.

One of the things I appreciate the most are people who refuse to be anti-utopian. We need more people to recognise that utopia is possible; it's possible for things to get better. We cannot give in to the hopelessness.

Immediately many people will object that this is too hard, too implausible, contradictory to human nature, politically impossible, uneconomical, and so on. Yeah yeah. Here we see the shift from cruel optimism to stupid pessimism, or call it fashionable pessimism, or simply cynicism. It’s very easy to object to the utopian turn by invoking some poorly-defined but seemingly omnipresent reality principle. Well-off people do this all the time.